Advancements in the Objective-C runtime

Description: Dive into the microscopic world of low-level bits and bytes that underlie every Objective-C and Swift class. Find out how recent changes to internal data structures, method lists, and tagged pointers provide better performance and lower memory usage. We’ll demonstrate how to recognize and fix crashes in code that depend on internal details, and show you how to keep your code unaffected by changes to the runtime.

Class data structure changes

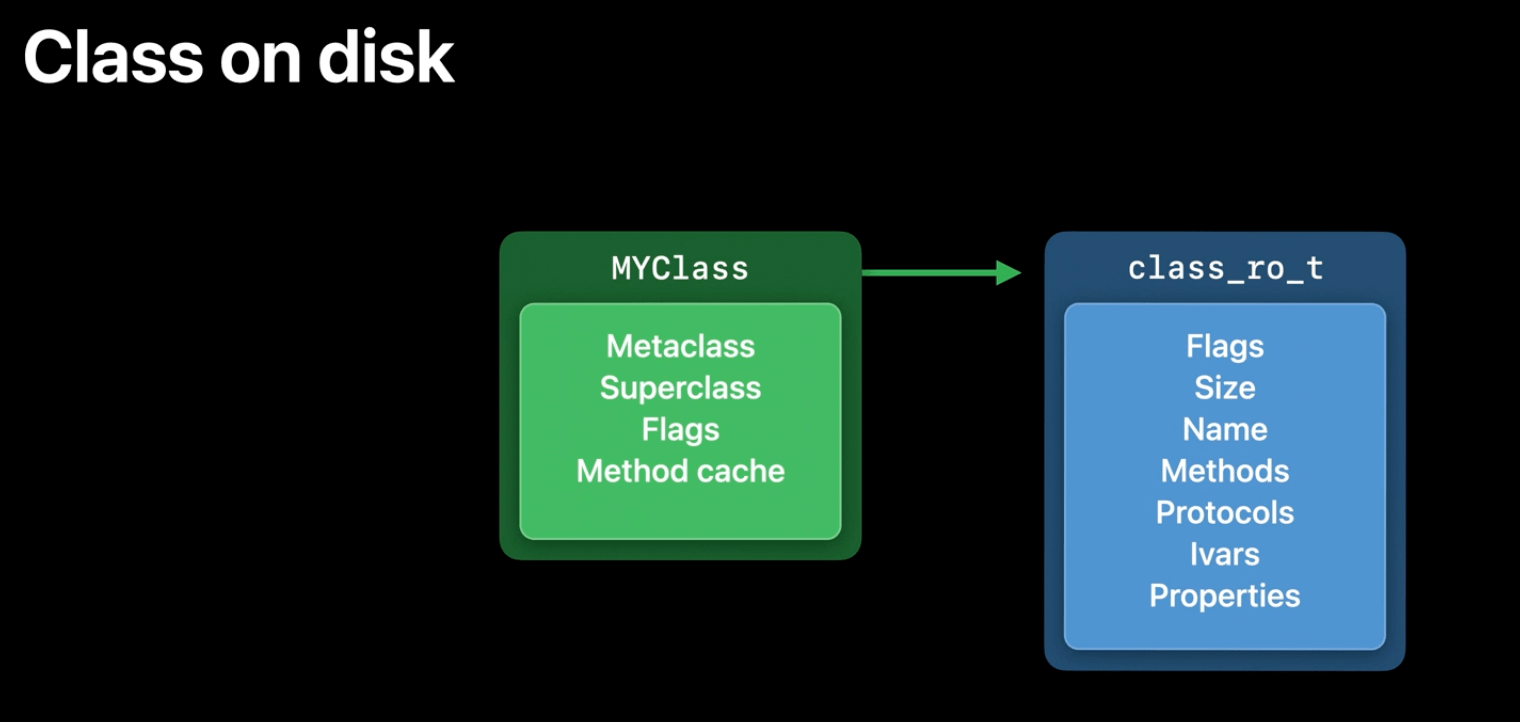

Class on disk

Every class structure in your application binary (on disk), both Swift and Objective-C, is represented by a class object, which contains the information that's most frequently accessed:

pointers to the metaclass, superclass, flags, and the method cache.

This object also has a pointer to more data where additional information is stored, called the class_ro_t (ro stands for read only).

This contains things like size, class name, methods, protocols, ivars, properties.

Clean vs dirty memory

- Clean memory is memory that isn’t changed once it’s loaded

class_ro_tis clean because it’s read only

- dirty memory is memory that’s changed while the process is running

- The class structure is dirtied once the class gets used because the runtime writes new data into it

- Dirty memory is much more expensive than clean memory

- It has to be kept around for as long as the process is running

- Clean memory can be evicted to make room for other things, because you if you need it, the system can always just reload it from disk

- macOS has the option to swap out dirty memory, but dirty memory is especially costly in iOS because it doesn’t use swap

- The more data that can be kept clean, the better

- By separating out data that never changes, that allows for most of the class data to be kept as clean memory

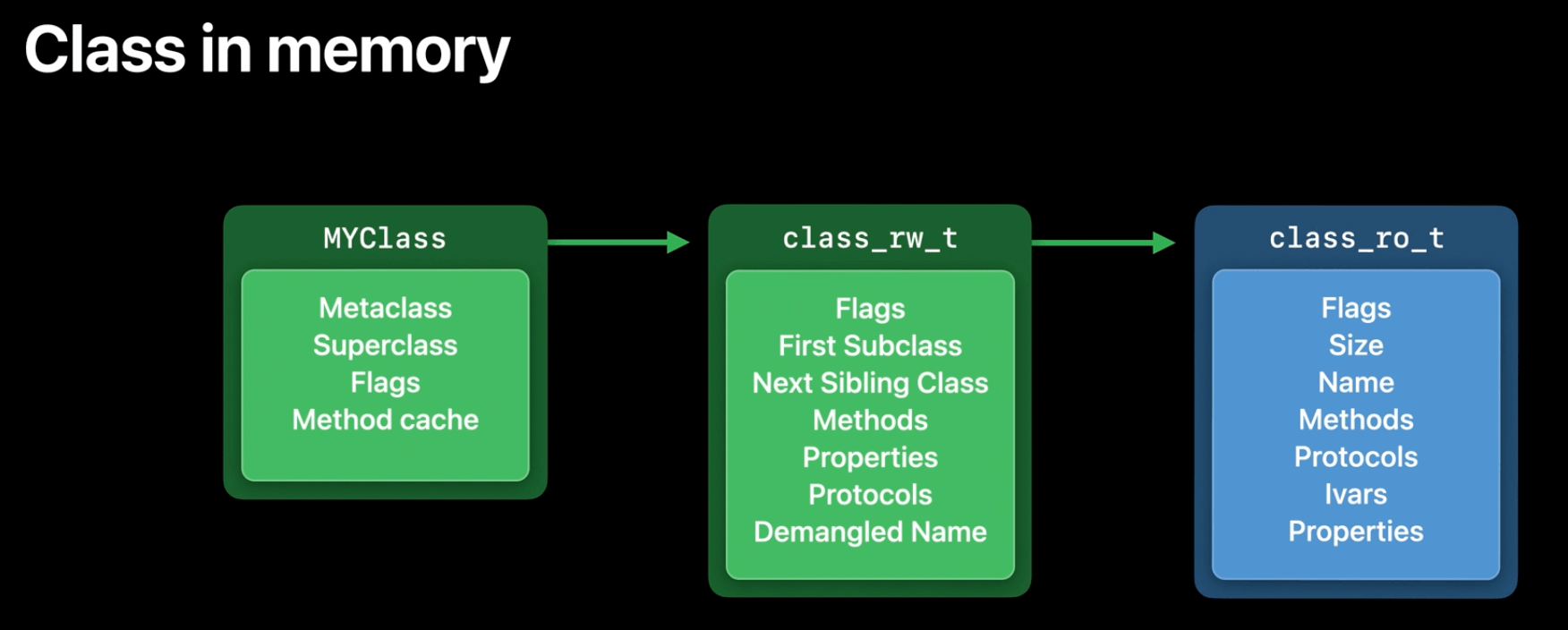

Class in memory

When classes are first loaded from disk into memory, they start off like this too, but they change once they're used.

When a class first gets used, the runtime allocates additional storage for it. This runtime allocated storage is the class_rw_t (read/write data).

In this data structure, we store new information only generated at runtime.

For example, all classes get linked into a tree structure using these First Subclass and Next Sibling Class pointers, and this allows the runtime to traverse all the classes currently in use, which is useful for invalidating method caches.

Why do we have methods and properties here when they're in the read only data too?

Because they can be changed at runtime:

- when a category is loaded, it can add new methods to the class

- developers can add/replace methods dynamically using runtime APIs

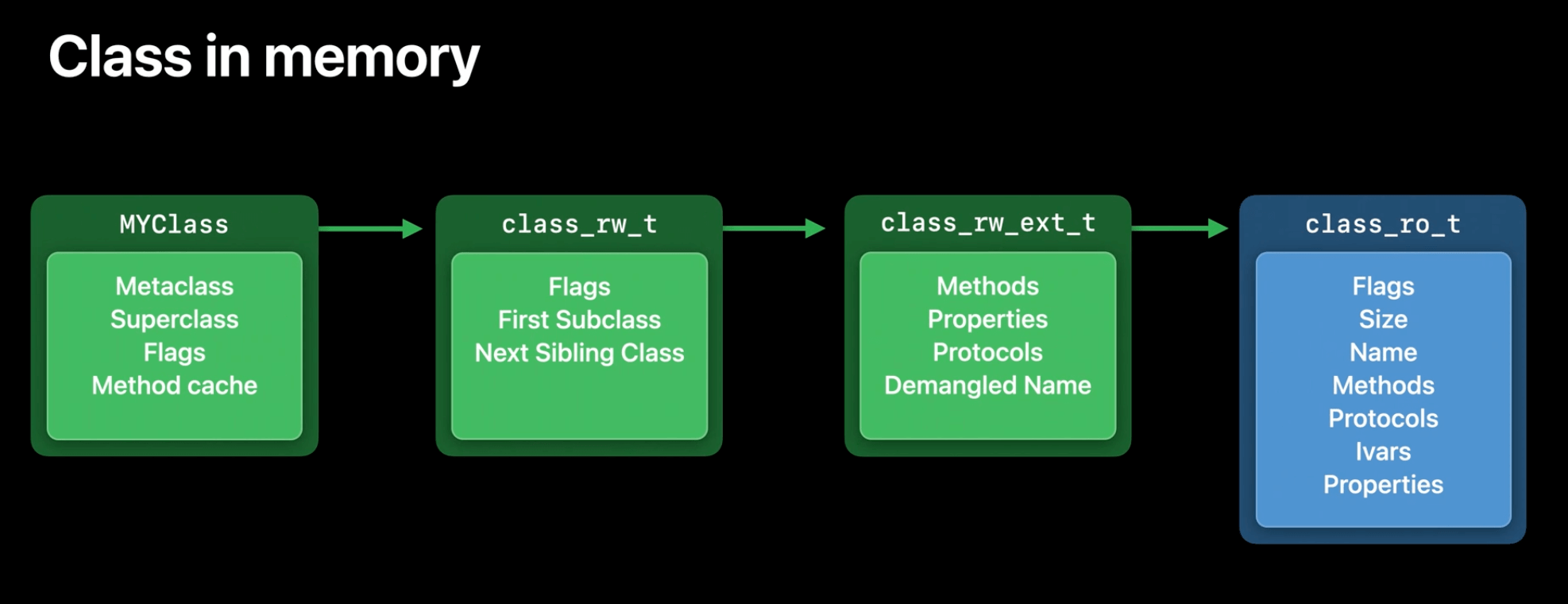

Updates

- iOS alone had about 30 MB of these

class_rw_tstructures across the system on an iPhone - by examining usage on real devices, Apple found that only around 10% of classes ever actually have their methods changed

- new this year,

class_rw_tis split off from the parts that aren't usually used, thanks to a newclass_rw_ext_t - Approximately 90% of classes never need this extended data, saving around 14 megabytes system wide

Relative method lists

- Every class has a list of methods attached to it

- The runtime uses these lists to resolve message sends

- Each method contains three pieces of information:

- the method's name or selector - selectors are strings, but they're unique so they can be compared using pointer equality

- the method's type encoding - this is a string that represents the parameter and return types, and it isn't used for sending messages, but it's needed for things like runtime introspection and message forwarding

- the pointer to the method's implementation - the actual code for the method. When you write a method, it gets compiled into a C function with your implementation in it, and then the entry in the method list points to that function

Updates

- if we look at a 64-bit system, all its memory addresses are 64 bit

- when we define a method, that method pointer used to be an absolute 64-bit address (8 byte per pointer)

- however that pointer needed to be resolved by the dynamic linker when the app was loaded

- those pointers also only ever points to method implementations within that binary, so they never really use all 64 bits of the address

- From this year, all these pointers are:

- 32-bit

- relative to the offset within the binary

- Advantages:

- offset address stays the same, regardless where they're loaded in memory (no extra work from dynamic linker). Which also means they can be move to read-only memory

- memory taken is halved

Tagged pointer format changes (on arm64)

Object pointer layout:

Address: 0x00000001003041e0

In memory:

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0001 0000 0000 0011 0000 0100 0001 1110 0000

- The lowest three bits are always zeroes, because of alignment requirements: objects must always be located at an address that's a multiple of the pointer size

- the high bits (the first few bytes) are also always zero, because the address space is limited.

We can take an address and change one of those bits that are always zero and flip it into a 1:

xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxx1

This will tell us that the address is not a regular pointer, and then we can assign other meaning to all of the other bits.

This is what tagged pointers are.

For example Apple could teach NSNumber how to read those bits, and teach the runtime to handle the tagged pointers appropriately, the rest of the system can treat these things like object pointers and never know the difference.

This saves the system the overhead of allocating a tiny number object for every case like NSNumber.

Tagged pointers on Intel

on arm it's the same, but flipped.

xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxx1

- The lowest bit is one, to tell apart normal pointers from tagged pointers

- The next three bits of that byte are what is called a

tagnumber, which indicates the type of the tagged pointer - the rest is the payload

As there are three tag bits, there are 8 (2^3) possible tag types:

OBJC_TAG_NSAtom = 0,

OBJC_TAG_1 = 1,

OBJC_TAG_NSString = 2,

OBJC_TAG_NSNumber = 3,

OBJC_TAG_NSIndexPath = 4,

OBJC_TAG_NSManagedObjectID = 5,

OBJC_TAG_NSDate = 6,

OBJC_TAG_7 = 7

OBJC_TAG_7is a special case that is called "extended tag", in this case the tag takes two more bytes, allowing 256 (=2^8) more tag types, at the cost of a smaller payload (2 bytes less)OBJC_TAG_7is used for example forUIColors andNSIndexSets

Updates

- on arm, the 3 bits tag have moved to the bottom three bits (like on Intel)

- everything else, including the extended tag, just shifted

1xxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx xxxx

- thanks to this change and how arm pointers are read, a tagged pointer can contain a normal pointer in its payload

- this opens up the ability for a tagged pointer to refer to constant data in your binary such as strings or other data structures that would otherwise have to occupy dirty memory

GitHub

GitHub

zntfdr.dev

zntfdr.dev